Blog

Named entity processing in a nutshell

Tue, 12.06 2018 —Trading zone part 1: Named Entity Processing. This blog post is part of Stepping in the NLP / History trading zone: a series of posts.

To put it very briefly, named entity processing corresponds to the tasks of:

-

recognizing mentions of entities of interest in texts and classifying them according to a set of predefined categories, usually Person, Organisation and Location, with more less specification (collective vs. individual person, geographical vs. administrative location)

-

linking these mentions to unique identifiers in order to deal with homographic names (“John Smith”) referring to different entities and name variants referring to the same entity. This process is also called named entity disambiguation

-

identifying relations between entities such as born_in between a person and a location entity, colleague_of between two persons, alma_mater between a person and an organisation (in this case could be of subtype ‘Educational’), etc.

For example, if someone is interested in studying the coverage and the commemoration of the battle of Arnhem in european newspapers, one starting point would be to identify articles mentioning the British army officer Bernard Montgomery. Naturally, running the query ‘Montgomery’ on a text search engine and filtering the results by date would already support the constitution of a potentially relevant sub-corpus, composed of articles containing ‘Montgomery’ and published at the time of or after the battle. However, if this query is already a giant step towards efficient search within large corpus of historical newspapers, the retrieved sub-corpus is still hardly usable because of, firstly, its size (e.g. the query [Montgomery apres:1939] on letempsarchives.ch returns 13,899 results) and, secondly, its inadequacy w.r.t the entity looked up, with fal se positive articles mentioning the place in Alabama, a american swimmer, a company in Zurich, a TV actor, a guitarist, etc.

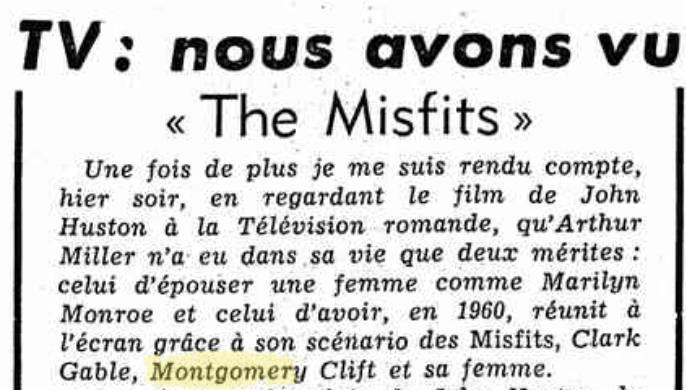

Below are examples of false positives for the query ‘Montgomery’:

False positive for the query ‘Montgomery’, intended for the Marechal JDG-1968-05-09

False positive for the query ‘Montgomery’, intended for the Marechal JDG-1968-06-25

False positive for the query ‘Montgomery’, intended for the Marechal JDG-1969-06-11

False positive for the query ‘Montgomery’, intended for the Marechal JDG-1969-08-28

A way to filter such false positives would be to query the string “Maréchal Montgomery”, but then the results will suffer from the inverse drawback of false negatives, i.e. missing articles where the field marshal is mentioned without its title or differently.

False negative for the query ‘Maréchal Montgomery’ JDG-1943-01-11

With the recognition, classification and linking (or disambiguation) of entities, the user could not only look for a entity of type Person containing the string ‘Montgomery’ (filtering out all Montgomery places), but also directly spot articles where the mentioned entity was linked to the unique identifier of the field marshal (e.g. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernard_Montgomery), therefore retrieving all articles mentioning this person, regardless of the lexicalisation (e.g. Maréchal Montgoméry, Montgomery, le général Montgoméry, le feld-maréchal Montgomery) and, potentially, of the OCR mistakes.

Example of name variant JDG-1944-06-15

Example of name variant JDG-1943-01-11

Concretely speaking, the impresso interface will allow search on entities (i.e. by referent) and on mentions (i.e. words which we know are names of entities), will offer entity network visualization and exploration capacities (e.g. to allow the selection of articles where Montgomery - referring to the marechal - and Arnhem - referring to the battle - are co-mentioned), and provide newspaper collection statistical profiles.

The technologies to perform such entity-related tasks perform well for general domain, contemporary English text, with ca. 90/95 entities out of 100 being correctly recognized, and 80/85 correctly disambiguated. The whole challenge here is to reach acceptable performance (meaning useful for historical research) on noisy historical text and to devise workflows which make the most of them.

Ehrmann, Maud. Named entity processing in a nutshell, Blog post, impresso, 2018 <http://impresso-project.ch/news/2018/06/12/tradingzone-ner.html>.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

A Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 (CC BY-ND 4.0) license applies to all contents published in impresso. While articles published on impresso can be copied by anyone for noncommercial purposes if proper credit is given, all materials are published under an open-access license with authors retaining full and permanent ownership of their work.